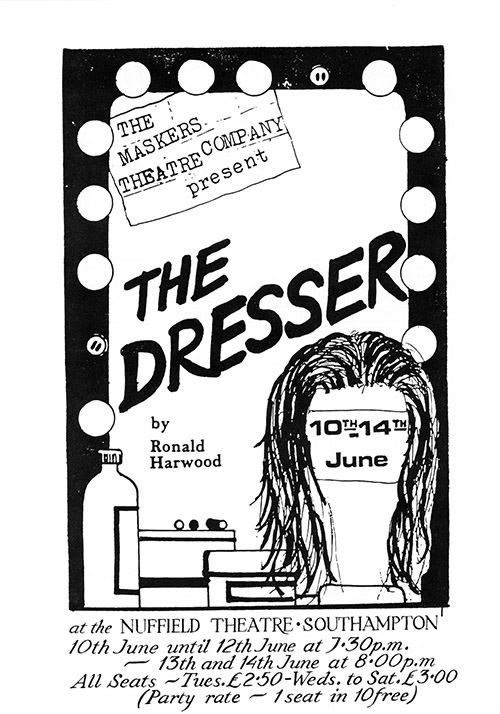

The Nuffield Theatre

on10th to 14th June 1986

The Dresser

Because I was Sir Donald Wolfit’s dresser for almost five years, it may be thought that the actor-manager in my play is a portrait of Wolfit, and that his relationship with his dresser is a dramatised account of our relationship. There may be other reasons for such a supposition : Lear was Wolfit’s greatest performance - so it is Sir’s; the grand manner both on and off the stage which Wolfit often employed is also Sir’s way; the war did not stop Wolfit from playing Shakespeare in the principal provincial cities and in London; Sir is on tour in 1942, though playing less important dates. But there the similarities, and others less important, all wholly deliberate on my part, end. Sir is not Donald Wolfit. My biography of the actor, with all its imperfections, must serve to reflect my understanding of him as a man and as a theatrical creature.

There is no denying, however, that my memory of what took place night after night in Wolfit’s dressing room is part of the inspiration of the play. I witnessed at close quarters a great actor preparing for a dozen or more major classical roles which included Oedipus, Lear, Macbeth and Valpone. I was an observer also of the day-to-day responsibilities which management demanded and, later, as Wolfit’s business manager partook of those responsibilities. I was a member of the crew who created the storm in King Lear which, however tempestuous, was never loud enough for Wolfit, as it never is for Sir. These and other countless memories fed my imaginings while writing the play. Sources of another kind were of equal importance. I was fortunate, when young, to meet Sir John Martin-Harvey’s stage manager; I held two long conversations with Charles Doran, the actor-manager who gave Wolfit his first job; I shared a dressing room with an old actor, Malcolm Watson, who walked on in Sir Henry Irving’s production of Becket at the Lyceum; I worked with several old Bensonians - members of Sir Frank Benson’s Shakespearean Company - and I knew Robert Atkins who, for many years, ran the seasons at the Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park. A number of the actors Wolfit employed were what used to be called ‘Shakespeareans’, men and women who had played with actor-managers not on the front rank. The atmosphere engendered by these men, imbibed by me before I was 20, was much in my mind when writing the play.

The tradition of actor-management made a deep impression on me. I came to understand that from the early 18th century until the late 1930’s the actor-manager was the British theatre. He played from one end of the country to the other, taking his repertoire to the people. Only a handful ever reached London; their stamping-ground was the provinces and they toured under awful physical conditions, undertaking long, uncomfortable railway journeys on Sundays, spending many hours waiting for their connections in the cold at Crewe. They developed profound resources of strength, essential if they were to survive. They worshipped Shakespeare, believed in the theatre as a cultural and educative force, and saw themselves as public servants. Nowadays, we allow ourselves to laugh at them a little and there is no denying that their obsessions and single-mindedness often made them ridiculous; we are inclined to write them off as megalomaniacs and hams; we accept, too readily I think, that their motto was ‘le théâtre c’est moi!’.

The truth of the matter is that many of them were extraordinary and talented men; their gifts enhanced the art of acting; they nursed and kept alive a classical repertoire which is the envy of the world, and created a magnificent tradition which is the foundation of our present day theatrical inheritance.

I must acknowledge also words written by and about them : Sir John Martin-Harvey’s excellent autobiography from which I have quoted in the play, the works of James Agate, the biography of Irving by Laurence Irving and J.C. Trewin’s splendid book, The Theatre Since 1900. The play, however, is called The Dresser. No actor-manager ever survived entirely through his own efforts. Publicly he liked to proclaim pride in his individuality while acknowledging, in private, his debt to all those who devoted their lives to him and to his enterprise. The character of Norman is in no way autobiographical. He, like Sir, is an amalgam of three or four men I met who served leading actors as professional dressers. Norman’s relationship with Sir is not mine with Wolfit. No other character in the play is wholly based on a real person. Her Ladyship is quite unlike Rosalind Iden (Lady Wolfit). I have considered it necessary to make these disclaimers in order to give a truer background to the play. I know to my cost that once a mistaken interpretation attaches to a work of imagination it is difficult, if not impossible, to dispel.

Ronald Harwood

| Cast (in order of appearance) | |

| Norman | Ken Hann |

| Her Ladyship | Lynda Edwards |

| Irene | Alice Hartley |

| Madge | Julie Baker |

| Sir | Terry Wiseman |

| Geoffrey Thornton | David Bartlett |

| Mr Oxenby | Derek Sealey |

| Players In ‘King Lear’ | Sheana Carrington, Fay Wiseman, Gardner Chalmers, Graham Hill, Harry Manns |

| For the Maskers: | |

| Director | Mollie Manns |

| Assisted by | Christine Baker |

| Stage Nanager | Joy Wingfield |

| Sound | Lawrence Gee |

| Assisted by | Edwin Beecroft |

| Lighting | Ron Tillyer |

| Set Design | Ken Spencer |

| Set Construction | Ken Spencer, John Riggs |

| Properties | Edwin Beecroft |

| Assisted by | Sheana Carrington, Philippa Taylor |

| Wardrobe | Sarah Buchanan, Fay Wiseman |

| Artwork | Graham Hill, Graham Buchanan |

| Wigs by | ’Showbiz’ |